Strasbourg, October 2021

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) is a body of experts attached to the Council of Europe that monitors the treatment of people in detention. They have the unique right to visit places of detention in Council of Europe member states and to talk privately with detainees. CPT visits form the basis of reports that are addressed to the state concerned. These are generally published along with the state’s response to the findings and recommendations, although publication is at the request of the state concerned and there is no obligation to make the report available to the public. In between visits, the CPT attempts to pursue their recommendations through dialogue with state representatives. The CPT is regularly updated by Öcalan’s lawyers, who believe that the organisation could be much more strategic and forceful in pushing Turkey to adopt the recommendations that come out of these visits.

The CPT has made nine visits to İmralı Prison, beginning in March 1999, two weeks after Öcalan’s capture and detention.

From the start, they raised concerns about Öcalan’s isolation and lack of contact with other prisoners. After that first visit, they warned that, ‘additional measures are required to counter the potentially negative effects on Mr Öcalan’s mental health of being held on his own in a remote location under a high security regime. Those measures relate inter alia to his possibilities for contact with the outside world and the precise nature of the regime applied to him.’ They stressed the importance of access to books, newspapers, and radio (which he received), and of ensuring that his family and lawyers were actually able to visit him as the rules allowed. They called for various improvements in his regime, such as more access to better outside space, and recommended that ‘the possibility be explored of transferring to İmralı one or more other prisoners, and that Mr Öcalan be allowed to associate with the prisoner(s) concerned.’

After their second visit, in September 2001, the CPT underlined that ‘the present, exceptional, custodial arrangements for Abdullah Öcalan cannot be allowed to continue indefinitely.’ They called for Öcalan to be given telephone access and to be allowed to correspond in private with the European Court of Human Rights and with his lawyer. They called for him to be allowed a radio with access to more channels and a television, and, again, for contact with other prisoners. The response from the Turkish authorities was ‘oppositional’ on practically all points raised.

The CPT’s third visit, in February 2003, was triggered by reports of the difficulties encountered by Öcalan’s lawyers and family when they attempted to visit him. Prison regulations state that he is allowed an hour’s visit each week from his lawyer and every other week from his family, but visits were frequently being cancelled with the excuse that the weather was too bad for the designated boat or that the boat was out of repair. The CPT found the situation unacceptable, and compounded by the lack of progress on their other recommendations to improve Öcalan’s contact with the outside world. They called for a better vessel to be available as needed and for flexibility over visiting days when the weather was rough.

On their next visit, which didn’t take place until May 2007, the CPT found that Öcalan was suffering a distinct deterioration in his mental health connected with ‘a situation of chronic stress and prolonged social and emotional isolation, coupled with a feeling of abandonment and disappointment’, and they argued that the only way this situation could be reversed was ‘through a fundamental change in the prisoner’s human environment and the ending of his social and emotional isolation’. They concluded, ‘The Turkish authorities are now at a crossroads: either they make no changes in the prisoner’s situation (which is the course they have deliberately and knowingly chosen since 1999, with the consequences described above), or they take the decision to review Abdullah Öcalan’s situation, allowing him, in particular, the possibility of maintaining basic social and emotional ties.’ And they reiterated their call that Öcalan be integrated ‘into a setting where contacts with other inmates and a wider range of activities are possible’.

The report further observed that, despite the purchase of a new vessel, visits from family and lawyers were still very irregular, and that, following new legislation brought in in June 2005, interviews with his lawyers were being recorded and he was subject to new disciplinary punishments, which his lawyers were not allowed to contest. He had still been given no access to a telephone, so, outwith his irregular visits, his only contacts with the outside world were three books from the library, three censored newspapers (provided days or weeks late) and a radio tuned to only one station.

The CPT delegation also took samples of Öcalan’s hair in order to carry out their own analysis following reports from his lawyers that he had been subjected to progressive poisoning. The CPT experts were not concerned at the levels of chemicals found, but they did recommend continued monitoring.

In 2008, frustrated at Turkey’s failure to act on any of their requests, the CPT set in motion processes for making a public statement on the issues, whereupon Turkey announced plans to construct a new detention block on the island, which would also house a limited number of other prisoners. In November 2009 Ocalan was moved into the new block along with five further prisoners, also serving life without parole, who were transferred to the Island from other prisons.

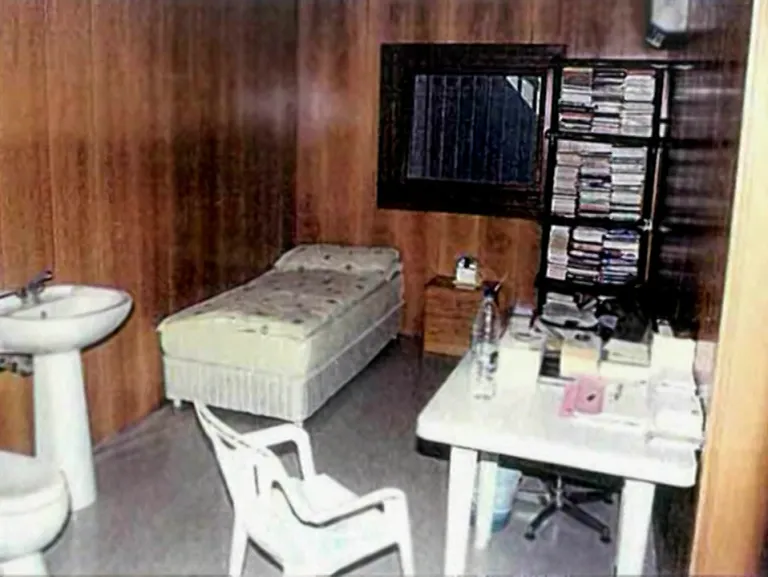

In January 2010, the CPT came to inspect the new facilities and arrangements. They found the cells well-constructed but devoid of natural light due to the 7m high walls surrounding their attached yards. Now there were other prisoners on the island, but communal activities were very limited – occasional sport and a one-hour conversation period a week in the presence of prison officers. For Öcalan, this was only ‘a very modest step in the right direction’. For the other prisoners, it was a big step back from what they had been used to before coming to İmralı. Following the CPT’s complaints, the authorities agreed to make operational changes to allow some more communal hours, but still refused Öcalan a telephone or television.

When the CPT next visited, in January 2013, Öcalan had been denied any visits from his lawyer since July 2011. Family visits, which were meant to be an hour, were being cut down to 30-45 minutes. Despite previous promises, İmralı prisoners were still very restricted in the time they were allowed to spend together – two hours sport, three hours conversation, and a possible three further hours of activity which the prisoners were rejecting in protest that they were only allowed to do this in pairs. In 2011 Öcalan had been forced to spend 240 days in solitary confinement – twelve disciplinary punishments had been saved up and then imposed back-to-back. Athough Öcalan had finally been allowed a television, he still had no telephone.

The CPT drew attention to the Council of Europe’s recommendation that ‘life-sentenced prisoners should not be segregated from

other prisoners on the sole ground of their sentence’ and asked the Turkish authorities to ‘reconsider their policy vis-à-vis prisoners sentenced to aggravated life imprisonment… and amend the relevant legislation accordingly.’

When a CPT delegation visited İmralı in April 2016, they found that Öcalan had been allowed more space through joining three cells together, but that, despite assurances from the Justice Minister, almost no progress had been made to meet the CPT’s recommendations on communal activities and on visits. Worse, not only had Öcalan still been allowed no visits from his lawyers, since 6 October 2014 he had been allowed no visits from his family either. There had been visits from MPs as part of the peace process, but these had stopped after 5 April 2015. By this time there were only three other prisoners on the island, apart from Öcalan.

The CPT’s next visit to İmralı took place in May 2019 while thousands of Kurds were on hunger strike calling for an end to Öcalan’s isolation. The report reminded Turkey of the CPT’s still unanswered call for an overhaul of the detention regime; and it noted that there had been no improvement, since their 2016 visit, in the İmarlı prisoners’ ability to socialise, despite specific recommendations. The four prisoners were being held in solitary confinement for 159 out of 168 hours a week, and only allowed to talk to each other during the three hours specifically allocated to conversation. The report again called on Turkey to ‘take steps without further delay to ensure that all prisoners held at Imralı Prison are allowed to associate together during daily outdoor exercise, as well as during all other out-of-cell activities.’

The 2019 report observed that lack of contact with the outside world ‘has been the subject of a long-standing intense dialogue between the CPT and Turkish authorities’. At the time it was written – following the hunger strike – there appeared to be slight improvements in external contact – including five visits by Öcalan’s lawyers – but improvements were soon reversed, and the isolation is more complete now than it has ever been.

With total lack of contact with İmralı for one and a half years after the brief phone call between Öcalan and his brother in March 2021, there were many attempts by different concerned groups to persuade the CPT to make another visit. They are the only organisation that can insist on doing this, and – apart from everything else – allay recurring fears as to Öcalan’s wellbeing. On 3 October 2022 the CPT released a statement saying they had made a visit in late September ‘in order to examine the treatment and conditions of detention of all (four) prisoners currently held in the establishment.’ And ‘particular attention was paid to the communal activities offered to the prisoners and their contacts with the outside world.’ Publication of the final report could take 12-18 months, and may not happen at all if Turkey does not consent. Öcalan’s lawyers argue that given the circumstances of his isolation the CPT have a duty to release information on his safety and health.